A cultural walking tour of Colombo

Lord Shiva (on his vehicle of the holy cow), his wife Parvati and their sons Ganeshan and Murugan above the entrance to the Sri Ponnambalam Vanesar Kovil on the port side

I remember being struck by John Gimlette’s observation in his book “Elephant Complex” that the people of Colombo had no collective word to describe themselves. They were neither a Colomban or a Colombite or anything else for that matter. Everyone it seemed was from the village or place of their ancestors. It made me think that the ethnic conflict which had marred most of Sri Lanka’s recent past was a testimony to the country’s inability find some collective identity amongst the many differences of its people.

And yet, when I walked through parts of old central Colombo on a cultural walking tour with Pepper, I glimpsed at ways of worshipping and being which suggested, as always, that the truth was far more complicated. Our guide Arshad skilfully navigated the monuments and streets revealing the nuanced interconnections between the places both historically and culturally. It was a walk which opened my eyes to some of the lesser known jewels of central Colombo.

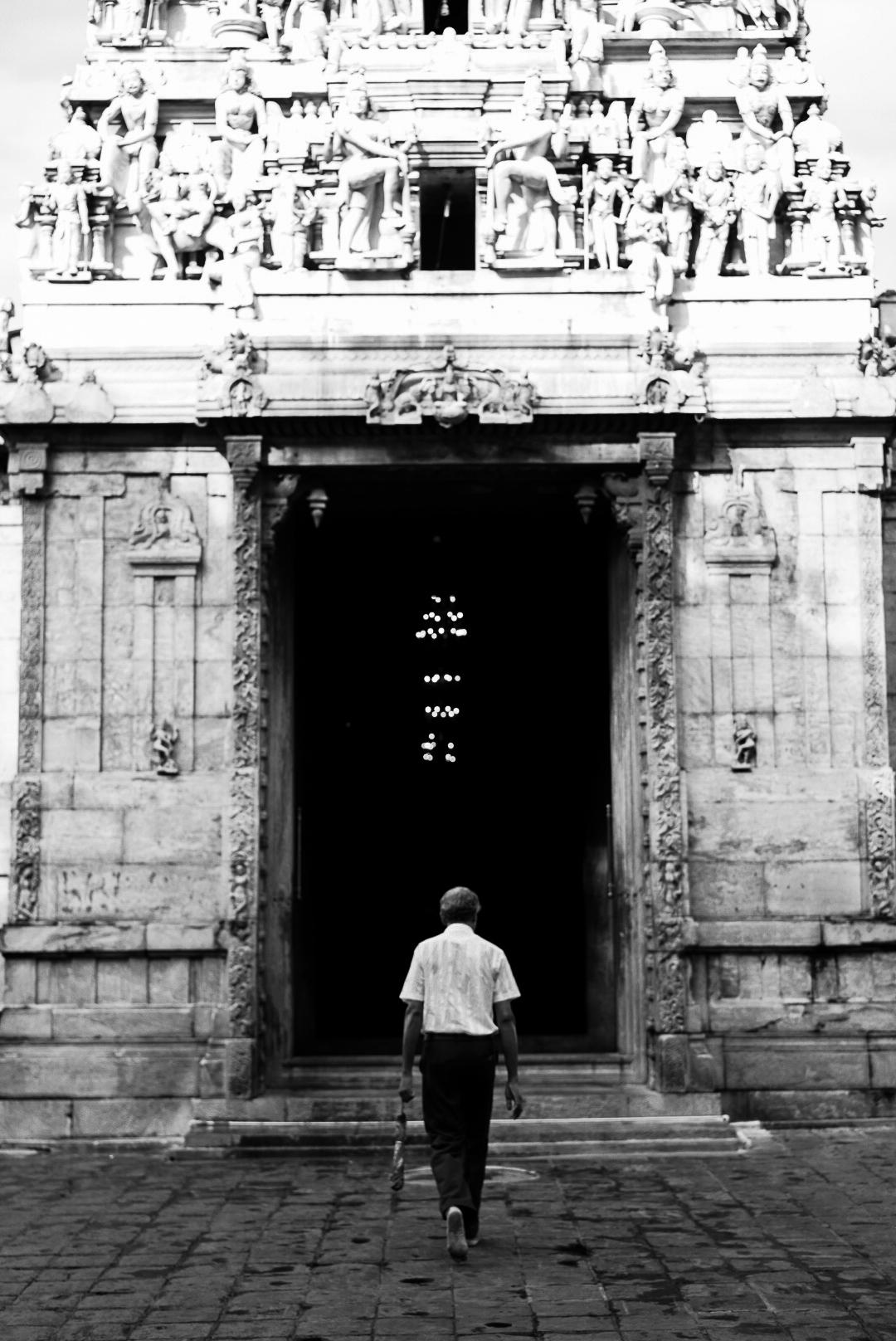

We started the Colombo’s Culture walking tour at the Sri Ponnambalam Vanesar Kovil close to the ports in Colombo 13, a part of town that few tourists traverse. This impressive structure built around 1900 and dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva was alive that day with morning worshippers on their way to work. I was instantly glad that our tour group was small so that we didn’t disturb their daily ritual. What’s not obvious, although Arshad alludes to it, is that the kovil belongs predominantly to Tamil Sri Lankans (although not all Tamil Sri Lankans are Hindu) and is a testimony to their culture and religious practice. The kovil itself was built according to the strict design principles of Hindu temples, which in this case included transporting granite all the way from South India to help seal its authenticity.

A funeral urn ornamentally placed in front of the red and white striped wall

Lord Shiva’s vehicle is the sacred cow and is kept on the premises

The ornate kovil roof without colour signifying Shiva’s role as “the destroyer”

Part of the threshold into the kovil made from South Indian granite

The distinctive red and white striped wall lets people know that this is a kovil

Following Arshad’s instructions, we carefully overstepped the threshold and entered the most beguiling parts inside the kovil. The intricately carved granite columns blackened by century-old flame-smoke now deceptively looking like wood, the brass pedestal holding gleaming bowls of golden coloured turmeric, crushed red rose petals and black ash used for marking one’s forehead with the third eye (as a means of self-reflection and inner discovery) and the shards of sunlight penetrating the darkness from spaced partitions in the roof. It’s so atmospheric.

As we walked through, I thought about some of the overlapping cultural elements, like the granite column configuration which was reminiscent of the audience halls in the ancient sites of Polonnaruwa and the similarities to a Buddhist temple of entering the complex with bare feet or the flowers, fruits and fire in the puja offerings.

Our next stop was the nearby St Anthony’s Church, whose origins are about 100 years earlier than the Sri Ponnambalam Vanesar Kovil at a time when the Dutch colonialists were oppressing all things relating to their predecessor Portuguese colonists, including their Catholic faith. Arshad tells a great tale of Fr. Antonio’s clandestine struggles to keep Roman Catholicism alive in Sri Lanka, the drama caused by the Dutch discovering this and the assistance given by the local fishermen in exchange for miracles to prove the existence of God. Of course, the miracles prevailed and the rest, as they say, is history.

But what I loved the most was how the church had embraced and absorbed the local culture, including the tradition of offering flowers which were laid at the feet of the Christian icons and the white string (typically a blessing offered by Buddhist monks) which was wrapped around structures holding the icon. Add to that the fact that all Sri Lankan ethnicities worship at this church and even those of other faiths will drop by from time to time to ask for favours, make vows or give thanks. It’s a true melting pot.

An unexpected joy of this walk was a short foray through some of the alleyways of Pettah. I had heard so much about these places but neither knew how to find them nor had I the courage to look. In these alleyways, people still live humbly cheek by jowl but have brightened their cramped spaces with vibrant colours which sing loud and proud about their homes. Arshad showed us how each door indicated the owner’s religion and that even a short alleyway had people of several faiths closely living and intermingling.

While the grand Tamil chettiars of Sea Street, Colombo 11 (or Pettah) still peddle their gold wares alongside yet more kovils and flower shops, the Sea Street of today seemed sadly diminished in size to the one I vividly remember my uncle taking me to in my teens. The street then was bursting with gold stores, salesmen at the door beckoning you to approach and the glistening gold almost blinding you in the midday sun. I am sure this is partly an overblown, rosy memory, but I couldn’t help but wonder if the demise I sensed was in some part due to the many years of ethnic unrest where those who had the means to leave, did.

The mini thali at Sri Surya’s Hotel

A pit stop for brunch at Sri Surya’s Hotel (“hotel” in the local vernacular also having the meaning of “restaurant”) in Pettah was a welcome change of pace. We could choose whatever we wanted from the menu, but Arshad recommended the mini thali which had a good selection of Tamil food specialties from the restaurant including vadai, thosai and idli which I washed down with a very Sri Lankan beverage of woodapple cream finished off by a masala chai. Expect to eat authentically with your fingers (but of course ask for cutlery if you don’t feel comfortable with this) and learn how to properly cool a hot masala chai before drinking by pouring rhythmically between your cup and bowl. I can confirm that it was all delicious!

Natural fibre donestic goods sourced from districts around Sri Lanka

Rounding a corner, we imperceptibly went from a predominantly Tamil Sri Lankan neighbourhood to a predominantly Muslim Sri Lankan one and closer to the more commercial heart of Pettah. We glimpsed the splendidly named Edinburgh Hall adjacent to the Old Town Hall and once its auditorium. The periphery of the hall was once grand ornate iron arches which you can still make out today if you look carefully enough but sadly these have been largely boarded up to house a market of household domestic goods purveyors, including one fabulous store which sourced products made from natural fibres from districts all over Sri Lanka. Pettah truly is the one place in Sri Lanka where you can literally buy anything.

Back on Main St I spied a street vendor selling achcharu (pickled fruits and vegetables with lovely sour/salty/chilli flavours) and managed to quickly purchase some for the road before we arrived at the Jami Ul-Afar Mosque – also known as the Red Mosque – built around the same time as the Sri Ponnambalam Vanesar Kovil. Clearly the turn of the last century was a peak time for consolidating community and identity in this part of Colombo.

The achacaru specialties on Main Street. May favourite was the pineapple on the bottom left.

Famed to resemble a pomegranate, the Red Mosque is a motley crew of architectural styles borrowing from Indo-Islamic, Indian, Gothic and Neoclassical genres to create its impressive structure. I learnt from Arshad that the mosque was painted in its famous red and white geometry to reflect the colours of the then British colonial flag! He also gave us a fascinating cultural insight into the physical movements during Muslim prayer and their proximity to five standard yoga positions which are connected with Hinduism and Buddhism. At this revelation, I half-wished that we had gone into the Red Mosque in the same way as we did with the church and the kovil but it was already close to 3 hours into our walking tour and we still had one last destination to cover, the Buddhist space of the Seema Malaka in Colombo 2.

Traditionally a sima malaka was a bounded, elevated terrace which was important in Buddhist monastic architecture as it gave monks a demarcated congregational space to meet and carry out religious administrative duties. The original Seema Malaka (a part of the Gangaramaya Temple around the corner) slowly sunk into the Beira Lake and a new structure was commissioned in the 1970s. It makes me smile that the designer was the non-Buddhist, and Sri Lanka’s famed architect, Geoffrey Bawa and that its construction was funded by a Muslim Sri Lankan named S. H. Moosajee and his wife.

Bawa’s architectural finesse is evident in the refined simplicity of the main structure (the adjacent meditation hall and the stupa were not a part of the original design) alongside the drama of the vibrant blue roof tiles allowing the structure to become one with the lake. It helps to fulfil the purpose of this Seema Malaka as a place for meditation and rest. Arshad explained the universal nature of some of the symbolism found there from the many Buddha statues with yoga poses, the flower offerings at the shrine to the carved moonstone at the entrance to the main hall. It really brought home to me the fragments of shared culture of Colombo’s people, whatever they choose to call themselves.

You’ve probably realised by now that I really enjoyed this walking tour with Pepper. Not only was it a well thought-out and fascinating route but our guide was very informative and had an obvious passion and an understanding of his city beyond the superficial. Everything on the tour was included in the price and extras like water bottles, shawls to cover shoulders at the kovil and even socks (if you’re reluctant to walk bare feet at religious sites) are all provided. I would definitely recommend it as a way of getting to know Colombo in your travels.