History of ceylon tea: Plain tales from the hills

I am kicking myself for forgetting something very important in my tale of Empire. Black versus green. No, no, it’s got nothing to do with rugby although that too was a British colonial export. I’m talking about an almost century-long shift from a world of green tea drinkers to one which drank predominantly black tea. I haven’t quite worked out whether it was clever strategy or dumb luck (likely both) but that change in tea preference turned out to be a useful one. The British needed its tea customers to swap from Chinese produced tea to that produced by its colonies and it was that love affair with black tea that clinched the deal.

I must admit to feeling a bit sorry for the Chinese in the tale of Empire and my sympathies lie with them in the Opium Wars and its aftermath. However, I am conflicted by my own love of strong black tea and my allegiance to Sri Lanka. You see, for Ceylon, the perfect storm had arrived.

In 1869, the dreaded coffee rust fungus was discovered in Ceylon’s then lucrative coffee plantations and within 15 years the blight (exacerbated by falling coffee commodity prices) had swept 100,000 acres of coffee cultivation out of existence, leaving the plantations in Ceylon abandoned.

Fortune however was on the side of a young Scotsman named James Taylor. Coincidentally in 1867, Taylor was pioneering the cultivation of tea bushes from Assam on 19 acres of land on the Loolecondera estate (located in a mountain range south of Kandy, Loolecondera is an English corruption of the words loola kandura meaning a gorge which contains “loola” or striped snakehead fish). Taylor was single-minded, scientific in approach and, like most pioneers, a workaholic. He was determined to make better tea than found in Assam. His efforts paid off and by 1873 Taylor had devised his own mechanical roller which enabled him to sell his first consignment of tea to London. Taylor’s success eventually resulted in the Loolecondera estate commercially growing tea on around 300 acres by the time coffee was no longer cultivated in Ceylon in 1885.

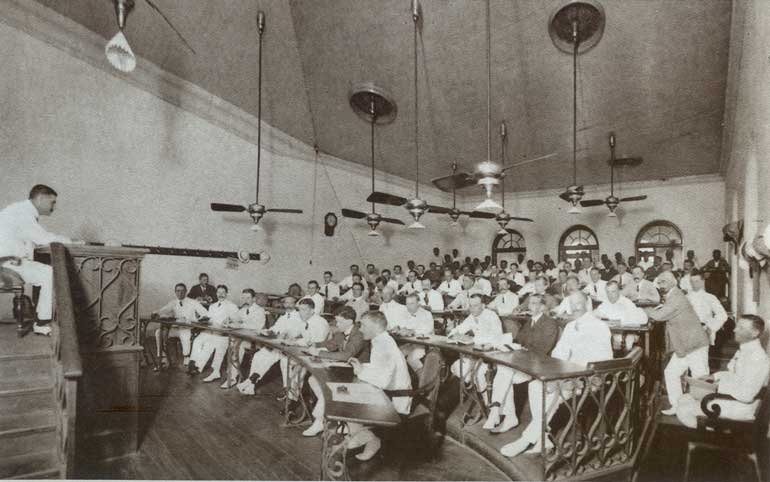

British planters at a tasting of Ceylon tea at the tea estate

The confluence of high altitudes, long rainy seasons and humidity made central Ceylon the perfect growing conditions for tea. Very soon the transformation of abandoned coffee plantations into tea estates gained momentum and with that roads and railways were built between the estates back to Colombo, Tamil labourers were imported from southern India in their thousands and eventually tea plantations covered the central highlands and south-central provinces of Sri Lanka like lawn.

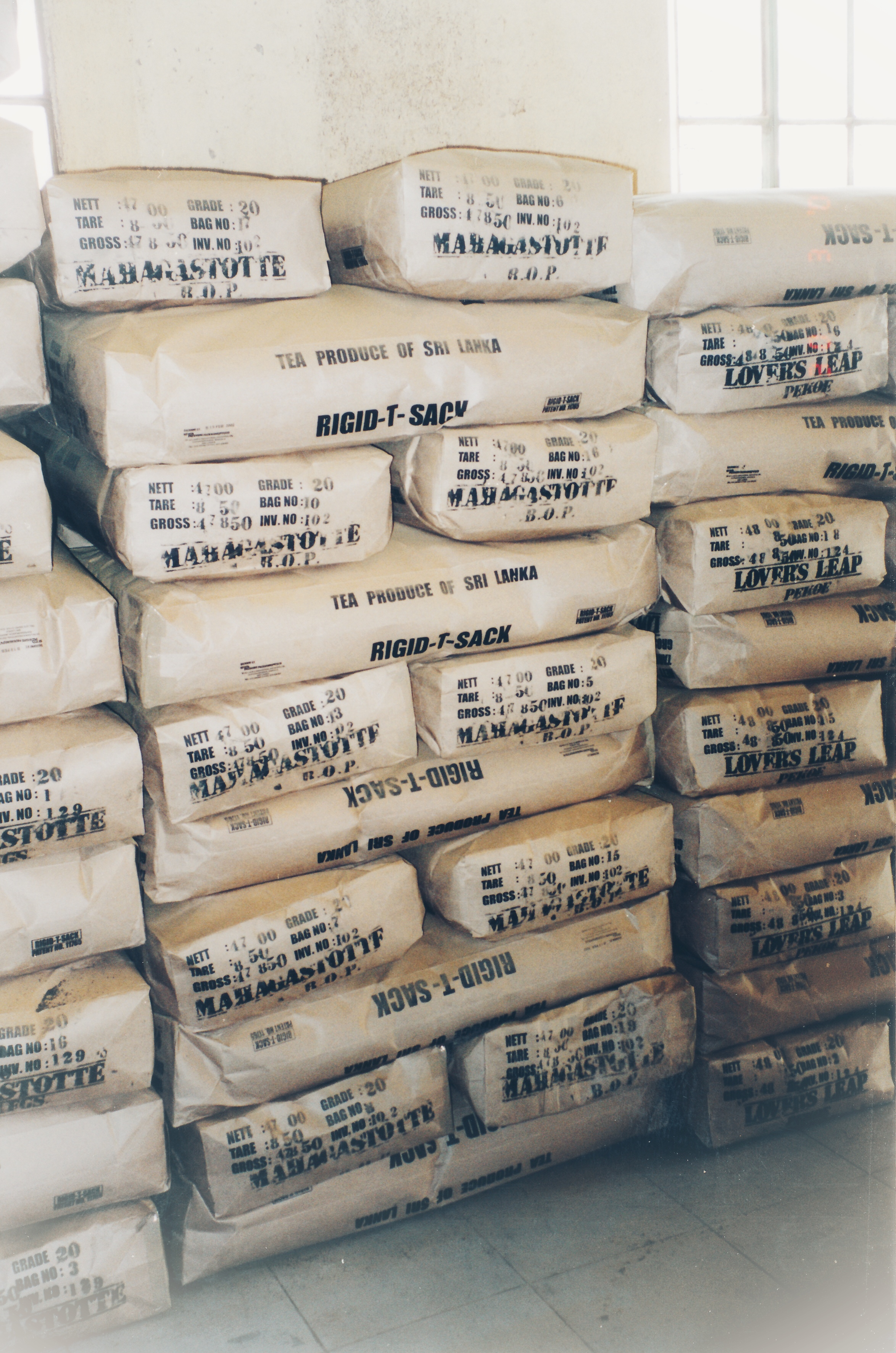

To give you an indication of the magnitude and pace of this change, Ceylonese tea exports increased from 900 metric tonnes in 1884 to 68,000 metric tonnes in 1900, with Sri Lanka and India together supplying 90% of the West’s tea by this time and taking China’s position as top dog. By the time Sri Lanka alone became the world’s largest tea exporter in 1965, its tea exports exceeded 200,000 metric tonnes.

The tea industry (including ancillary services such as packaging, warehousing, etc and the extensive administration services associated with it) gradually usurped Ceylon’s traditional agrarian style economy with its feudal system of land tenure, tenancy and subsistence farming. Assisted by new British legislation, it flagged a turning point towards Sri Lanka’s modernity. Businesses sprung up in the Colombo metropolis and even the Kandyans (rightfully suspicious of this feverish British attitude to commerce) slowly changed their minds when they saw the wealthy estate owners among the coastal Sinhalese.

Prior to European occupation, the Ceylonese elite had been scholars and monks, warriors and chieftains who enforced dues and service to the king. But the British way of life took root in the hills and even the local gentry began to emulate the British with their cricket, tennis, horse racing, golf, fishing and gentleman's clubs. A dying legacy of this era is the archaic, turn-of-the-century British English adopted by the locals. I remember an uncle of mine once angrily referring to someone as a blackguard (pronounced “bla-ged” in the British way, but with a Sri Lankan accent) and to one of his old friends as a batchmate. It still makes me smile. At least two generations of Sri Lankans had adopted a British way of life and were more British than the British.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s hard not to have mixed feelings about these developments.

The first public Colombo Tea Auction was held in 1883at the premises of Somerville & Co. under the auspice of Ceylon Chamber of Commerce

A group photograph found amongst Henry Randolph Trafford's possessions of the Darrawella Club from the 1880s

Nostalgia somehow has a knack sweeping away uncomfortable details. Every time I go to the tea country (or “up country” as the locals call it) the scenery alone takes my breath away. My eyes feast on the misty landscapes, lush waterfalls, exotic flora and the rolling mountains dressed in dainty rows of perfectly manicured green. I have travelled for hours and have seen nothing but this, forgetting that it was all once thickly rainforested. I am taken in by the white multi-storeyed tea houses (or tea factories) of Victorian era industrial design suddenly rising from the hills, each bearing evocative colonial names like Havelock Road, Excelsior and Elephant Nook. I truly love these towering remnants of colonialism.

Then there’s the old railways built by the British which transport you through the landscape and back in time, helped along by the spicy Sri Lankan hawker food available on the journey. And it’s usually just another photo opportunity for the traveller but I also marvel at the colourful, sari-wearing Tamil tea pluckers dotted along the slopes. They manage to keep the vast expanse of bushes perfectly pruned with nothing but their bare hands. The history of tea ought to better account for their arduous work.

The tea endeavour in Ceylon was enormous in scale and impact making Ceylon’s contribution to the history of tea and, by virtue of that, to world history greater than you would reasonably expect for a tiny nation. Even as an expatriate, it is something I am proud of. You really should go and see for yourself or find yourself some fine Ceylon tea to drink. Either way, you won’t be disappointed.

![Film_view from [Pedro Estate] tea near Nuwara Eliya - David (2).jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59899fa9f9a61eda9f9f0394/1520911060234-OZZMN5DP3CEJFHC1CALO/Film_view+from+%5BPedro+Estate%5D+tea+near+Nuwara+Eliya+-+David+%282%29.jpg)