History of ceylon tea: A tale of empire

What’s the first word that pops into your head when you think of Ceylon? I’m betting that it’s tea. It’s not surprising really – it’s a common supermarket item. Behind that everyday product though is a swashbuckling tale of Ceylon’s role in the long history of tea and one which has, for better or worse, shaped the country of Sri Lanka today.

The history of tea is an almost mythical one dating back to around 2700 BCE but it’s the last 400 years where things get interesting. In those years, the history of tea is also the story of cotton, bullion and opium, conquests, revolutions and slow march towards globalisation.

Not that I had ever thought about it in those terms to be honest. I’d grown up a humble tea drinker – a strong “plain tea” (as my mother would call it) with a small slab of jaggery on the side, please. It’s intoxicating and a distinctively Sri Lankan thing to do in the receding heat of the afternoon. It’s very hard to ponder any matters of true tea significance at such moments. So Ceylon punching above its weight in modern world history on the back of its tea production came as a pleasant surprise.

King Rajasinha II (1608 - 1687), like many Sri Lankan kings, spent most of his time fighting off Europeans

I don’t think Ceylon set out to throw its weight around in world history. After all, its kings were not the marauding, sea-faring types. This greatness was thrust upon Ceylon when it was forced into the whirlpool of British colonialism. At the time though, the Brits were happily extracting their tea from the then world’s largest producer: China, leaving Ceylon to lead the world in coffee cultivation with not a tea plant in sight. Empire was the real reason the British stuck around in Ceylon. Serendipity had eventually delivered tea to Ceylon and it was Ceylon’s tea plantations (along with India’s) which financed the might of that British empire in its last hundred years.

Before I start, would you like to make yourself a cup of Ceylon tea for this story? The tale of empire deserves a good brew.

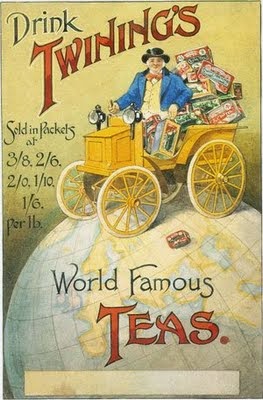

The fact is that the British empire started off rather unceremoniously in 1600 with a handful of shrewd, private individuals. They created the now famous colonial trading enterprise, the East India Company. Tea wasn’t on the top of East India Company’s investment hit list but by the time the British upper classes had developed a taste for this new luxury called tea around 1700, the East India Company had managed to secure a monopoly on all trade with China from the British parliament. Of course, the East India Company then saturated the London market with tea, allowing prices to drop and creating a tea drinking explosion amongst the masses.

The craze for tea was aided and abetted by the ingenious idea of adding sugar to tea. Luckily for them, the cost of sugar was coming down too. This addictive concoction caffeine and calories turned tea drinking into the quintessential British cultural pastime, reaching its zenith in the Victorian era when the British took tea in the morning, at lunch, in the afternoon and at supper. It became the epitome of a bourgeois, civilised life. The British wasted no time promoting this tea culture to its overseas colonies, especially in North America. I’m still impressed at how British imperialism and prestige were subtly reinforced every time a simple cup of tea was offered. Demand for tea soared and the East India Company along with the British Crown (through its taxes) made out like bandits.

The underbelly of this story is how unscrupulous the East India Company and Britain became in order to maintain their gravy train. The fact was that the East India Company was essentially paying for its Chinese goods (mainly tea but also silk) with cotton taken from India following its conquest. It was a direct transfer of wealth from India to Britain through the latter’s trade with China.

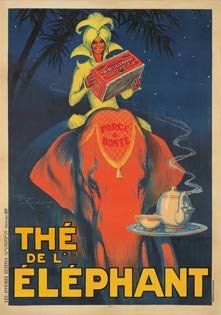

The fly in this ointment however was falling cotton prices. Quite simply, the trade in cotton was no longer enough to pay for all the demand in tea. Normally, silver would have been used to pay for the Chinese goods, but the East India Company has been busy waging war on the side over the years, using its silver to fund that endeavour. It was low on stocks of silver bullion and nervous about spending what it had in the face of a world silver shortage. So what does a super-successful colonial trader do in such circumstances I wonder? It calls home and asks for help. The British parliament obliged by granting the East India Company another monopoly, this time over the trade in opium grown in India. Lo and behold, smuggling opium into China to pay for tea became part of the trade. The illegal opium trade unsurprisingly proved a boon, soon creating a trade surplus in favour of the British and once again the imperial coffers filled up quickly. The Chinese were however floundering in an opium-induced mess which led to the Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860) and left the British searching for more viable sources of tea production.

India (again) was an obvious choice partly because the tea plant “camellia sinensis” was discovered late in the piece to be indigenous to its north-western region of Assam. However, it’s one thing to have a wild plant and another thing altogether to have a product called tea. Over the centuries, the Chinese had selectively bred a better tea plant and jealously guarded its tea making processes so that first Assamese product made by the British was a failure. The British quietly engaged in some industrial espionage and eventually cracked that nut (or should I say leaf?), just in time too for Ceylon to make its entrance onto the world tea stage.

So, how’s your cup of Ceylon tea going? Has it put you in the mood to hear Ceylon’s tea story? Well you’ll need to stick around to find out. I told you it was a swashbuckling tale!

[READ PART 2 OF THIS ARTICLE HERE]