Tropical modernism: Sri Lanka’s stamp on world architecture

In Sri Lanka’s current travel boom, boutique hotels are a dime a dozen. But it wasn’t always this way. I remember a time when we would travel for miles only to stay at “rest houses” approved by the Sri Lankan Tourist Board because there just wasn’t much else on offer. Of course, those rest houses were perfectly fine and functional but hardly inspiring with their faintly bureaucratic uniformity. So you can imagine my awe when I first visited The Lighthouse Hotel in Galle about a year after it was first opened. I honestly thought someone had built a fort of luxury to show up that other real, and then somewhat decaying, Galle Fort down the road.

Looking back, I think I was just too young to understand why the imposing approach to this hotel which was interlocked onto the side of a rocky promontory almost stopped me in my tracks (“Are we allowed in?” I recall asking meekly) or why the iron balustrade of life-like warring Sinhalese and Portuguese figures encircling the entrance staircase bedazzled me or even why I felt like royalty perched on that open balcony of soaring ceilings and cobblestone facing the sea. All I remember sensing then was that even the crushing humidity had somehow magically vanished into thin air.

The iron balustrade on the entrance staircase was designed by Bawa's friend and artist Laki Senanayake. The staircase is reminiscent of the spiral staircases in lighthouses and was conceived by Laki as a swirling mass of Dutch and Sinhalese warriors re-enacting the Battle of Randeniya. Photo credit: Chic Locations

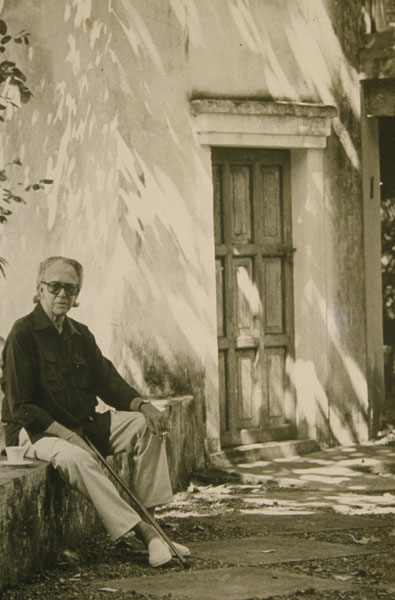

What words could not then describe but memory had deliciously savoured was the transformative effect of the bold and confident architectural style of tropical modernism. Back then I knew almost nothing of Geoffrey Bawa – the hotel’s architect – but he is the Sri Lankan, if not South Asian, poster boy for this architectural style. Bawa wasn’t the first in Sri Lanka to espouse it but he certainly was the most prolific and successful exponent.

Abandoning his first vocation as a lawyer and qualifying as an architect late at 38, Bawa designed some 35 hotels, office buildings, schools, orphanages, religious buildings and, his crowning achievement, Sri Lanka’s Parliament House (for an excellent photo essay on several of Bawa’s works check out designer Thomas Merkel). It is virtually impossible to visit Sri Lanka without experiencing a Bawa design or, indeed, designs which now consciously or otherwise emulate Bawa’s style.

To appreciate Bawa’s impact requires a working understanding of that much bandied around phrase: “tropical modernism”. As the name suggests, its origins lie in the Western architectural movement of modernism, which was fundamentally a desire to use the then new industrial technologies of glass, concrete and steel in a building’s structural design and construction, revolutionising it in that process. Aesthetically, modernists prized what we now simply take for granted – light, open plans and a sense of space. However, modernist architecture first designed for northern hemisphere conditions translated poorly to hot or humid climates. It took British architects Fry and Drew to first conceive the concept of “tropical” modernism in West Africa – they applied those modernist principles to enhance the building’s ventilation by integrating it with the environment and the climate. A truly inventive step which now appears almost obvious to contemporary minds.

The unlikely heroes of this story however are Sri Lanka’s early, globe-trotting architects (including Bawa) who championed this concept and innovated it to include local building traditions, aesthetic and craft into the design. What now seems so commonplace – resorts in South-East Asia with dove-tailing pavilions and “infinity pools”, private homes with “outdoor rooms”, towering ceiling heights, natural ventilation and light-infused spaces – is in no small part due to these Sri Lankan pioneers.

Visiting or staying at these Sri Lankan buildings as a part of your travels in Sri Lanka is the perfect way to see how tropical modernism has been given life. Here’s a taste of what I mean:

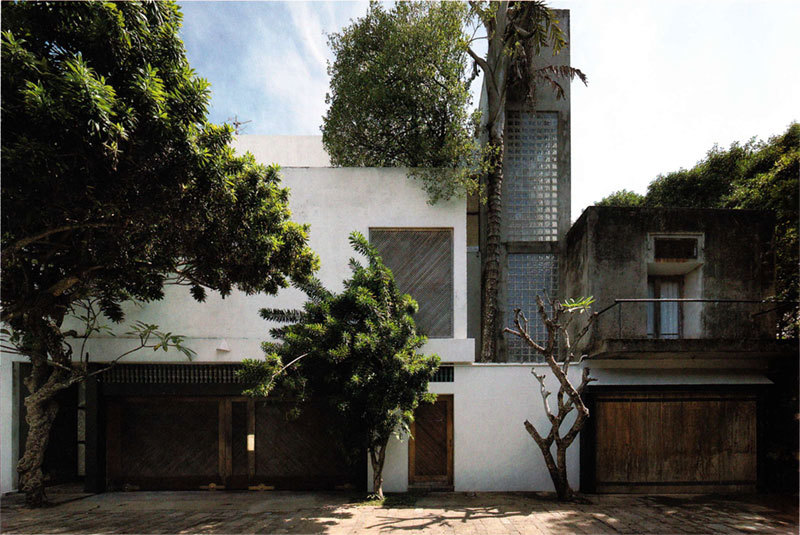

Kandyan Arts Centre (architect: Minette de Silva)

To my mind, Minette de Silva is the unsung hero of Sri Lankan architecture. De Silva’s ideas for interlocking spaces, championing local materials and handicrafts alongside modern technologies, central courtyards allowing free flow of air inside and out, pivoting staircases, triple height living spaces – to name a few – paved some of the way for the likes of Bawa (as you can read from this very illuminating account of her life and works). Despite this ingenuity, her difficult temperament, her apparent lack of technical skill, sexism towards women architects of her era (she was Sri Lanka’s first) and being eclipsed by Bawa’s singularly grand creations have all sadly contributed towards the ignorance and loss of her works with only a handful remaining – one of which is the Kandyan Arts Centre. Visit for a cultural performance to see flashes of de Silva’s brilliance. Taking inspiration from a Kandyan village, the entrance is followed by a progression of open and harmonious courtyards and pavilions under traditional tiled roofs leading to the dramatic, over-sailing, geometric timber roof originally designed to allow light and ventilation (unfortunately this part has since been altered to its detriment). Much of the materials were locally sourced and the people completing the handicraft work included women.

Kandalama Hotel, Dambulla (architect: Geoffrey Bawa)

Bawa had mastered the art of designing architecture which was co-extensive with the land, where the outside and inside blended seamlessly and water was a central motif. The Kandalama Hotel opened in 1991 is a classic example of the synthesis of these ideas. This hotel, designed to be hidden on approach, literally wraps itself around the western side of a cliff. A tunnel from reception has been forged through the rock leading to the open-air lobby which commands breathtaking views of the landscape. It’s designed so that the eyes follow an unbroken line of man-made pools to man-made lake and beyond towards Sigiriya and the Dambulla Caves, those famous rocks you’ve probably actually travelled here to see. The hotel’s flat roof is a nod to the dry-zone in which it exists and the greenery down its façade has the makings of a vertical garden, long before that became a “thing”. All these features contribute to its environmental sustainability along with the building's water sourced from deep wells which then is recycled and re-used on landscaping. For the traveller, the hotel preserves the aura of the ancient hermit caves and temples which were a feature of Sri Lanka’s golden ages, inviting you to retreat within it.

Mount Cinnamon, Mirissa (architect: C. Anjalendran)

If you want to know why the New York Times waxed lyrical about C. Anjalendran, you only need to have a peek at the magnificent private residences designed by him. Anjalendran worked with Bawa in Bawa's later years and his work met with Bawa's approval. Anjalendran championed the idea of the courtyard or internal garden as a means of privacy and providing the respite required by the hectic nature and often ugliness of the outside world. You can experience it for yourself by booking Mount Cinnamon, which is situated at the edge of a cliff overlooking Weligama Bay situated on Sri Lanka’s famous southern beaches. With a (very Sri Lankan) pitched roof and overhanging eaves, broad verandahs which become rooms themselves, insides opening to the outside, a beautifully enclosed courtyard, pavilions and, of course, the integration of water into the aesthetic, it is a haven born of ventilation and views.